By Erica Jackson, Predoctoral Fellow, and James Fabisak, Ph.D., Associate Professor

Center for Healthy Environments and Communities, School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh

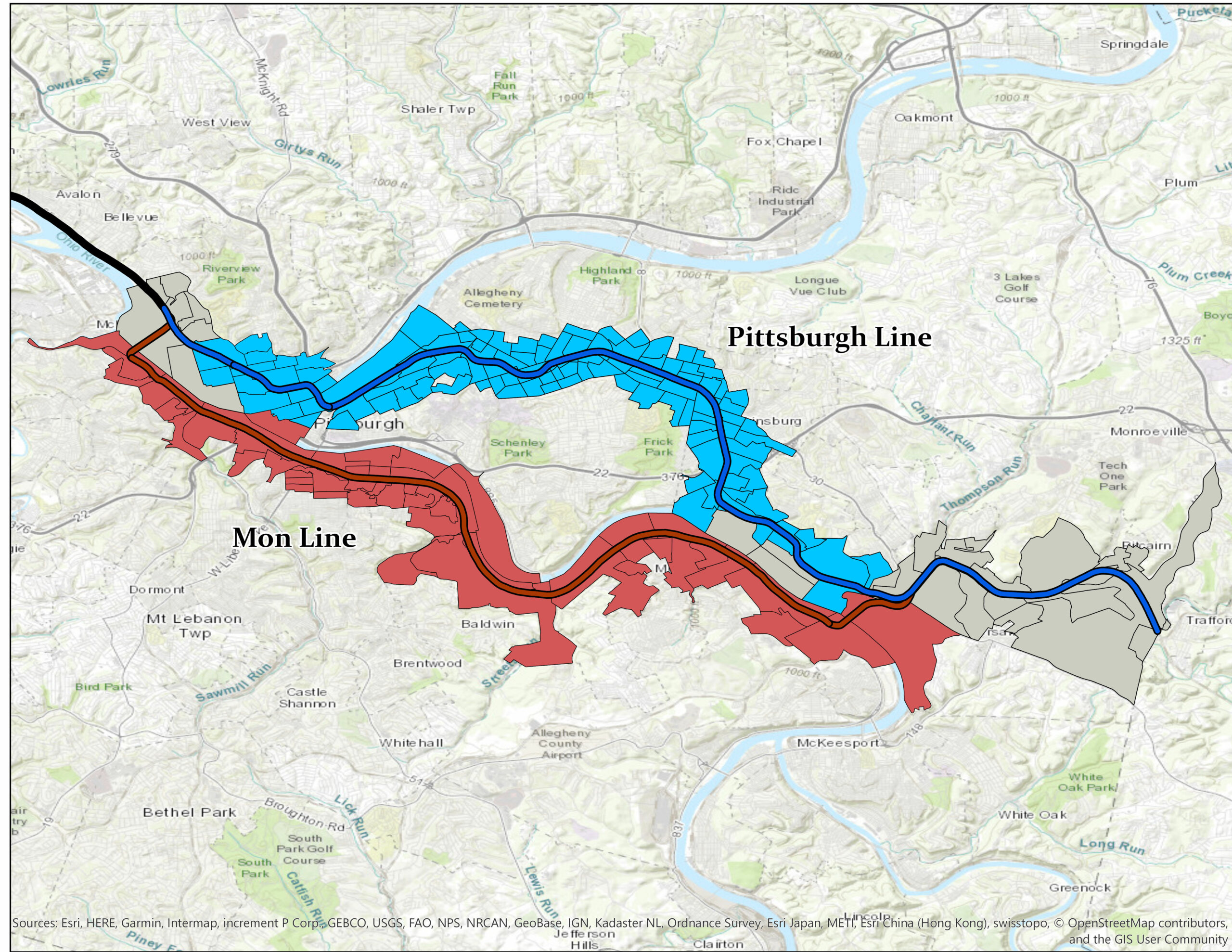

The Center for Healthy Environments and Communities at the University of Pittsburgh was approached by several concerned citizen groups and the Breathe Project inquiring what the health and air quality impacts might be for Pittsburgh and surrounding municipality neighborhoods from a recent proposal by Norfolk Southern railroad to increase traffic along the Pittsburgh Line (the black line in the above photo) from 20 – 30 trains/day currently to 40 – 50 and perhaps more.

This railway passes through Allegheny County beginning in Trafford, east of Pittsburgh, and continues through Homewood and up to Pittsburgh’s North Side until it merges with the Fort Wayne Line near the McKees Rocks Bridge. The proposal calls for increasing the number of trains on the Pittsburgh Line, and would also add double-stacked trains to this route, a move that would require infrastructural changes at over a dozen sites along the route to accommodate the taller trains.

We started by asking a few simple questions: 1) Who and how many would be impacted by the proposed Pittsburgh Line expansion; 2) Who and how many would be impacted by the alternative approach of adding traffic to the Mon Line; and 3) What are the potential risks involved?

Norfolk Southern already runs double-stacked trains along the south bank of the Monongahela River on the Mon Line. The Mon Line deviates from the Pittsburgh Line at East Pittsburgh, travels along the southern bank of the Monongahela River through South Side and rejoins it further west in Marshall Shadeland, creating two different railways through the city (see map).

The section of the Pittsburgh Line that is separate from the Mon Line is 16.9 miles, while the Mon Line is 17.6 miles. The idea to add double-stacked trains to the Pittsburgh Line came after a landslide on Mount Washington closed part of Mon Line for 11 days. With two double-stacked routes, more trains could pass through the city and transportation could continue if one railway is forced to close. Norfolk Southern also says that the Pittsburgh Line will save them three hours travel time. It is also likely that the proposal represents the goal of expanding rail traffic through the Pittsburgh region, perhaps in anticipation of the industrial expansion planned for oil, gas, and petrochemical activities in the Pa., West Virginia and Ohio tri-state area. If the proposal were rejected, additional traffic would likely be added to the existing Mon Line and other routes.

We estimate that there are 112,189 people living in close proximity* to the section of the Pittsburgh Line where double-stacked trains would be added. This represents 9% of the county’s population. Several thousand of them, however, live in areas that are equally impacted by the Mon Line, leaving 88,275 people (7% of the county) who would only experience an impact from trains on the Pittsburgh Line. The map (above) shows these impacted areas shaded in blue, and covers parts or all of the following neighborhoods: Marshall Shadeland, California Kirkbride, Central Northside, Manchester, Allegheny West, Allegheny Center, East Allegheny, North Shore, Downtown, Strip District, Polish Hill, North Oakland, Bloomfield, Shadyside, East Liberty, Larimer, Homewood West, Point Breeze North, Homewood South, and neighborhoods east of Pittsburgh including Wilkinsburg, Edgewood, Swissvale, Braddock, and East Pittsburgh. In grey are the neighborhoods impacted by both routes.

Of the 88,275 people exclusively impacted by the Pittsburgh line, 72% live in areas that qualify as “environmental justice” regions. This means that the census block (section of a neighborhood) that they live in has at least 30% or more non-white minority residents and/or at least 20% of residents living below the poverty line. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection designates these areas to receive extra consideration in policy decisions to ensure that they do not disproportionately shoulder the burden of environmental hazards, as is historically the case in minority and low-income communities. In the county as a whole, about 29% of the population lives in environmental justice census blocks. Therefore, at 72%, modification of the Pittsburgh Line would greatly and disproportionately impact environmental justice communities.

What if the Pittsburgh Line proposal were rejected, and additional traffic were added to the Mon Line? We estimate that 65,119 people live in close proximity to the Mon Line. Once again, several thousand of them would be impacted by either route, leaving 41,205 people that would only be impacted by increased traffic of double-stacked trains on the Mon Line. This number is only 3% of the county’s population, less than half the amount that would be affected by the Pittsburgh Line. Fifty-five percent of this population live in environmental justice blocks.

What are the risks? A main concern is air quality. Diesel engine trains emit a variety of air pollutants known to adversely affect human health, including volatile organic compounds, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxide. Particulate matter (PM) is of particular concern as Allegheny County received a failing grade from the American Lung Association for daily and long-term PM levels in 20184. The Pittsburgh Metropolitan Area ranks 10th and 8th worst for these respective pollutants out of nearly 200 metropolitan areas in the US. Furthermore, many of the people living along both the Pittsburgh and Mon Lines already reside in highest quartile zones of traffic–related pollution, based on exposure maps developed by Albert Presto at CMU.

About 20% of the mobile source emissions of diesel-derived primary PM2.5 (particulate matter less than or equal to 2.5 micrometers in diameter) in Allegheny County currently come from rail traffic, according to EPAs 2014 Emission Inventory. Using emission factors established by the EPA, we estimated that a typical 70-car diesel freight train traveling the approximately 20-mile Pittsburgh Line consumes about 150 gallons of fuel during the trip and releases approximately 405 grams of PM10 (particulate matter less than or equal to 10 micrometers in diameter). That is the equivalent of emissions from 68 diesel urban buses. Adding 20 trains per day to the Pittsburgh Line would be the equivalent of adding 1,360 buses. Double-stacked trains, however, have the potential to be much heavier, perhaps longer, use much more fuel, and consequently have much higher emissions. Adding 20 “monster” trains to the Pittsburgh Line could approach adding 6,800 busses per day to this route. Health concerns associated with PM include asthma, increased respiratory symptoms, cancer, and premature death from heart or lung disease. Diesel particulate matter (DPM) appears to be the largest single air pollutant driving cancer risk in Allegheny County9. Trains also emit carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change.

Additional risks could present themselves if the rail is carrying hazardous materials, such as industrial chemicals, ethanol, or petroleum10. If a train were to derail or experience an accident along the Pittsburgh Line, it would do so in a densely-populated area with many homes, schools, parks, and hospitals nearby, posing a significant public health threat. Noise pollution, traffic, and stress on existing infrastructure (including sewage and water lines) are also possible adverse effects.

Adding double-stacked trains to the Pittsburgh Line would directly impact the lives of 112,189 people, but thousands more would also experience impacts from generalized increased train traffic and a number of construction projects required to modify the railway. This route would impact more than twice as many people as the current Mon Line does, and many of those already live in vulnerable communities experiencing other environmental health hazards.

To be fair it should also be noted that hauling freight by rail results in less overall pollution than if it were carried similar distances by truck. Rail operators, however, should be cognizant that these decisions potentially concentrate that pollution over a relatively small area and potentially affect the health and well-being of a sizable population of Pittsburgh residents. Affected communities deserve a clear explanation of the rationale behind this decision before choosing to impact so many socio-economically disadvantaged people living in an area already at risk for air pollution health effects.

It is also important to consider the long-term implications of this proposal and how much overall rail traffic in the entire area could increase in the next decade. If this development is in response to the proposed hub of petrochemical expansion, it remains to be seen how Pittsburgh residents will accept associated impacts from this expansion. This analysis suggests that Norfolk Southern should work with the city and surrounding neighborhoods to facilitate open and transparent dialogues about the above issues, address the many concerns this proposal raises, and collaboratively strategize to effectively minimize the risks.

*Close-proximity is defined as living in a census block that intersects the railway or that has a geometric center within 0.5 miles of the railway

Census Data is from the 2016 American Community Survey 5-year Estimate.

Environmental justice data is from the PA DEP’s 2015 census block groups.